Rockin’ With The Walkingstick

Rockin’ With The Walkingstick

Rockin’ With The Walkingstick

By Doug Pifer

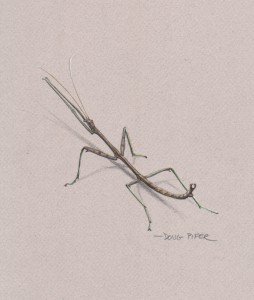

I found a walkingstick on the porch. I’ve loved these charming insects since I was a kid. Nearly three inches long, they look like animated twigs. And they rock!

Walkingsticks usually stay in the leafy canopy of shade trees, where they feed on the leaves of oak, cherry, basswood, and many other trees. Colors range from green to gray and various shades of brown among the females. Male walkingsticks are slightly smaller and tend to look more or less alike. What‘s remarkable is how much they look like thin twigs, right down to the tiniest details.

Walkingsticks seem to know they’re invisible in the trees. They remain motionless a long time, quietly munching leaves. Now and then they sway from side to side on their legs. Rocking may change speed or duration, and stops as suddenly as it starts. Sometimes they rock while walking, which really makes me laugh. It’s as if they’re jamming to music only they can hear.

Biologists debate why walkingsticks rock. Is it a response to disturbance? Does it serve to further camouflage the insect, imitating the sway of plants in the wind? It may be how the insect adjusts its vision and gauges distance while moving from place to place. No one seems to be sure. I’ve seen this behavior in other animals: praying mantises rock while stalking prey, some shorebirds walk with a rocking gait, and spiders rock when their webs are disturbed. But nobody rocks like a walking stick.

For walkingsticks life seems simple. They eat and they prefer the company of the opposite sex. Adult males wander until they find a female. The male hooks his claspers around the female’s abdomen and then stays that way, all the time. This isn’t just about sex—they seem to prefer life in tandem. Pairs feed, rest and move about, day and night, joined together.

As a kid I raised walkingsticks one summer. I built them a cage of window screen and fed them fresh tree leaves that I periodically sprinkled with water. At one point I kept six of them together, and for the most part they got along peacefully in connected pairs. If a single male approached a pair, the guys would slug it out, the stranger trying to knock the paired male off. The females dropped eggs randomly. These I kept over winter, and some hatched the following spring.

The glossy eggs were the size of flax seed, football shaped, coffee-brown with a light tan stripe. Walking through a woods in late summer where walkingsticks abound, you can hear their eggs hitting the forest floor with a patter like rain.

Walkingsticks sometimes become so numerous they can defoliate trees with their feeding. But since these wingless insects can’t travel far, it’s generally a local problem. Foresters say walkingsticks actually benefit the woodland environment by opening up the leafy canopy. Such openings allow sun to penetrate, stimulating plant growth and creating habitat diversity.