Program Honors High School’s First Black Graduate

By Dorothy Davis

In the annals of Clarke County history is the name of a young African American female whose name is recognized by only a few individuals — Mary Patricia “Pat” Reynolds. In 1965 Pat was the first Black graduate of Clarke County High School, thus ending the long saga of segregation in local public schools.

The United States Supreme Court mandated in a 1954 decision, Brown v. Board of Education, that public schools in this country should desegregate at a deliberate speed. However, the state of Virginia chose not to follow the law, but instead established “Massive Resistance,” which prohibited integration in public schools. Massive Resistance was mandated by the governor of Virginia and local politicians, which meant the obstruction of the federal law. Today, students hear this and say, “What?”

Meanwhile, students such as Patricia who desired a better education than that received at Johnson-Williams High School applied to enroll in CCHS. She realized supplies, equipment, and curricula were superior at CCHS. It was normal for used books to be passed on to JWHS after five years of use at CCHS. Having knowledge of such inequities and desiring a better education, Pat spoke with her mother, Mrs. Thomasine Maxwell, about transferring to Clarke County High School. After long, in depth discussions, Mrs. Reynolds acquiesced and, with mixed feelings, agreed to support her daughter in this new endeavor.

Patricia was strong, mature, and focused. She received few negative interactions at her new school. However, there was much pushback toward her mother from various aspects in the community for allowing her daughter to enroll at CCHS. Patricia graduated successfully with her class in 1965!

The Clarke County Public School System was officially integrated in 1967 — thirteen years after the 1954 federal order.A commemoration in honor of Mary Patricia Reynolds, who 50 years ago was the first Black graduate of CCHS, is scheduled for Friday, April 19 at 2pm at Johnson Williams Middle School Auditorium. The program is coordinated by the Reynolds family, the Clarke County Board of Education, the Clarke County Education Foundation and JWMS eighth grade class.

Anyone interested in donating to the Mary P. Reynolds Memorial Scholarship may do so by mailing a check payable to the Clarke County Education Foundation to PO Box 1252, Berryville, VA 22611. Or, donate online

at www.ccefinc.org/donate.

Why Native Plants?

By Wendy Dorsey

You may have noticed that lately there’s a buzz about native plants. Maybe you read an article or a post on Facebook, an advertisement for a native plant sale, or attended a presentation. In all of these instances, the message was the same. Putting native plants in our yards is a beneficial thing. There are many reasons why this is true.

Native plants are especially adapted to local temperatures, rainfall, and soil. With regards to temperature, they can make it through the coldest winter freezes and hot, dry summers — like the one we had last year.

I didn’t water most of the established (more than one full year in the ground) natives in my garden during the drought. I didn’t lose any! This has to do with the fact that these plants are able to survive on the amount of rainfall our region receives, even through the challenging extremes.

Many native plants have longer roots than non-natives. Because of this, they are able to reach water that the others cannot. Native plants are easier to maintain and conserve water. Our soil is most often clay, or clay dominant, but some land is rocky with poor soil. Others have wet spots to contend with. The good news is that there are native plants that want to live in each of the situations. Gardeners do not always have to amend their soil, it’s easier to select the species that will be happy with what you’ve got.

In order to survive, wildlife needs shelter and food sources. Native plants provide both of those. It is important that we put native plants in our yards to begin to counter the habitat loss that has been occurring in our country. The USDA Forest Service estimates 6,000 acres of open space are lost each day, a rate of 4 acres per minute. This includes forests, meadows, and wetlands. The wildlife is left without a place to live and the plants that sustained them.

Planting native protects biodiversity

Biodiversity is all the different kinds of life you’ll find in one area — the variety of animals, plants, fungi, and microorganisms like bacteria. Native plants and insects began coevolving millions of years ago. In this process of slowly changing and adapting to each other over time, many specialized relationships were formed. An example from our ecosystem is the monarch butterfly and milkweed. Animals and most insects avoid eating milkweed because of the toxins they contain. Monarch butterflies, however, lay their eggs on plants in the milkweed family. They do this because these are the only plants their caterpillars eat. The toxins do not bother the monarch caterpillars, but do help them survive by making them poisonous to predators. If we do not have milkweed, we do not have monarchs.

All kinds of caterpillars are crucial to keeping the balance in our ecosystem, not just the poster-child monarchs that are so wonderful to behold. The magnificent white oak tree hosts 952 caterpillar species, the most of all U.S. native trees. It’s easy to overlook this important fact, or maybe to even consider it a problem. Did you know that it takes 350 to 570 caterpillars every day to keep one nest of baby chickadees fed? To raise them until they are out of the nest, it takes between 6,000 to 9,000 caterpillars! Now consider that it is not just chickadees, but rather 96 percent of birds that raise their young on the same food source. Without host plants like white oak, we won’t have caterpillars and without caterpillars, we won’t have birds. Native plants improve the stability and resilience of an ecosystem.

Native plants support a healthy environment

They are far less susceptible to pests and diseases, and do not require pesticides and fertilizers. Money and time are saved by not having to purchase or apply them. Keeping chemical treatments out of our yards is better for us and all of the creatures that live in our ecosystem. Invasive plants, like autumn olive or English ivy are non-native plants that outcompete our native ones. In other words, they can take over an area, essentially displacing our local flora and the life forms that interact with them.

A healthy environment is one that also supports human life. Native flowers provide pollen and nectar for our native bees, wasps, flies and birds. There are specialized relationships between flower and pollinator. A great example is the hummingbird, with its long narrow beak. It is able to get the nectar from very long, tubular flowers. While doing this, the pollen gets on its beak and head and some of it will brush onto the next flower it visits. It is estimated that every 1 out of 3 bites of food exists because of insect and animal pollinators.

I encourage people to plant natives, flowers, shrubs, and trees, in their yards for all of the above reasons and more. What is most important is that every little bit matters. You don’t have to do a drastic, all-at-once makeover to your yard or property in order to make a difference. Start by adding one plant to your yard and encourage someone else to do so, too.Wendy Dorsey is the owner of Yellow House Natives in Berryville.

Three Things You Didn’t Know About Acupuncture

By Tara YG Wells

Let’s address the elephant in the room first: needles.

As an acupuncturist for 12 years and a promoter of it for 25, it always comes up. It’s mainly because our primary experience of needles is via the hypodermic of conventional medicine. They are big and hollow by nature as fluid must flow through them. Necessary, but not necessarily fun. Dry needling, a useful therapeutic technique used by physical therapists, also gets muddled in the mix.

Folks often tell me they’ve had acupuncture when actually they’ve received dry needling. The technique originated using hypodermic needles manipulating trigger points. Now physical therapists use a large solid needles to manipulate structure and release muscle tension. Great technique — not necessarily comfortable!

Acupuncture is different We use tiny filiform disposable needles that are roughly the diameter of a human hair. In all my years of practice, I’ve had many patients who are terrified of needles. And they have all been pleasantly surprised by how different acupuncture needles are.

The second thing you may not know about acupuncture is how well it dovetails with Western conventional medicine. Medicine in the 21st century in America is truly amazing. With tools like antibiotics, surgery and the treatment of cancer, it has extended lifespan and improved quality of life. An area where acupuncture really shines is supporting cancer patients during chemotherapy and radiation. Current cancer treatment is a modern miracle. And it can be challenging for the patient to make it through the protocols. Using acupuncture to support sleep, energy, and digestion during this necessary process can be highly supportive.

Currently, conventional medicine is less successful with chronic conditions such as diabetes, chronic pain, and insomnia. While medications are palliative for these conditions, there is also the consideration of medication side effects. This is where acupuncture comes into its own because acupuncture is, at its core, about building health and restoring proper function. East Asian medicine in general, and acupuncture specifically, is deeply rooted in common sense and the rhythms of daily life. What is the quality of our sleep? Our diet? Our relationships? Acupuncture combined with daily habits that promote health can give us a strong foundation to weather the challenges of daily modern living.

Which brings me to the fact that health doesn’t just happen. Health is something that we build or erode daily. It’s like the difference between health insurance and health care. Health insurance is like homeowner’s insurance: it’s a really good thing to have especially when a tree falls on your house. But it doesn’t take out the trash or clean the gutters.

On the other hand, health care isn’t just a yearly visit to primary care. Our blood work lab reports are a very useful medical innovation. However, health care is a combination of both how we live and the tools we use to stay healthy. And there are many ways to do this. Movement, diet, therapy, bodywork, and good sleep are some of its many components.

No matter our age, we are all aging. But as a culture, there are aspects of aging that we accept as “I’m just at that age now…”. Don’t get me wrong: we are all going to get older. But decreasing sleep quality, stiffness and poor digestion are optional.

In our modern world, we are constantly buffeted by a myriad of demands like work, family, relationships. And then there are the extraordinary demands of chronic illness or caring for someone with a chronic condition. The underpinning of all this is our health. Aging is mandatory- resilience is optional!

Curious about acupuncture? Consider coming to the Sanctuary Wellness Center for NADA Weekend Wind Down. The NADA ear acupuncture protocol uses five points in each ear to calm the nervous system and reduce stress. Once the points are placed in the ear, participants relax comfortably for 20 to 40 minutes.

Recipients of NADA report relief from stress and anxiety and improved mood and sleep. This technique has been used successfully to support mental well-being in situations ranging from counseling and recovery programs to natural disasters. Join us on Friday, April 12 from 5:30 to 7pm at the Sanctuary to experience this simple procedure and start your weekend off right!Tara Welty has more than 23 years experience as a practitioner of East Asian medical arts. Her extensive training includes traditional acupuncture, Jin Shin Jyutsu, gua sha, NADA auricular acupuncture and Plant Spirit Medicine. She practices at Sanctuary Wellness Center in Berryville.

Keep Clarke Clean For Earth Day and Every Day

By John Kei

The idea for an Earth Day event is simple – as is the mission of the Clarke County Litter Committee: Keep Clarke County Clean.

Ashley Harrison, who chairs the committee, has taken the lead for an Earth Day celebration on Saturday, April 20. “We hope to raise awareness of current litter issues and our efforts to reduce litter in our beautiful community,” she said. “We want to collaborate with others in this effort, work together on one day, and go out to gather as much litter as possible.”

“Earth Day Celebration & Litter Pick Up” begins at 9 a.m. April 20 at the Clarke County Ruritan Fairgrounds. After welcoming remarks from county and committee leaders, everyone will disperse to pick up litter in designated areas across the county, including the fairgrounds, Chet Hobert Park, and Rose Hill Park. Return to the fairgrounds by noon for refreshments, pizza, and a glass-crushing demonstration by Christi McMullen, who voluntarily initiated the county’s glass recycling program in 2022.

Another way residents and civic groups can help keep Clarke County clean is by adopting a stretch of road. According to keepvirginiabeautiful.org, every year “nearly 18,000 Adopt-a-Highway volunteers collect more than 25,000 bags of waste along Virginia’s highways. It is estimated that these efforts save the Commonwealth over $1.35 million that would have otherwise gone to clean up Virginia’s roads.”

The Clarke County Litter Committee adopted a road in the county through the Adopt-a-Highway program, but more roads need more volunteers.

“By volunteering to pick up litter along roadways, citizens are also helping VDOT,” said Harrison, explaining, “When VDOT crews spend time picking up litter, it is time, money, and effort that could be directed at more important road infrastructure issues. By adopting highways to clean up, volunteers help VDOT, our community, and the environment.”

Picking up trash is potentially saving wild animals, too, as they are constantly lured into roads by fast-food wrappers and then killed by vehicles. The “Adopt-a-Highway” program is simple. A group commits to a minimum two miles of a VDOT-maintained road, which in Clarke is every road in the county except private lanes and secondary streets in Berryville and Boyce.

“Adopt-a-Highway” also asks groups to commit to at least two cleanup days per calendar year and report their cleanups to VDOT. Adopt-a-Highway signs identify the groups that pick up litter. VDOT provides trash bags, safety equipment, and safety training. VDOT also collects the bags of trash after cleanups.

“It’s very simple, and I’m sure a lot of people may not even know how to adopt a stretch of road,” Harrison said. “Each community organization has its own mission, but I believe if everyone gave a few hours on a few days each year, we could make a big dent in collecting litter and cleaning our environment.”

To adopt a stretch of a Clarke County road, go www.vdot.virginia.gov/about/programs/aah. To learn more about the Clarke County Litter Committee, go to www.clarkecounty.gov/LitterCommittee.

Organizations, groups, and individuals who want to participate or need more information about the April 20 “Earth Day Celebration & Litter Pick Up” event should contact the Litter Committee at (540) 955-5132 or litterfree@clarkecounty.gov.

The Barns Story and a Chamber Award

by Diana Kincannon

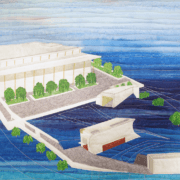

I recently received an honor of which I’m very proud: The 2023 Citizen of the Year Award from the Top of Virginia Chamber of Commerce. The award was in recognition of my years of work for the Barns of Rose Hill, a project to salvage two very old barns in Berryville’s town center and restore them for public service as a center for the arts, education, and community, and to establish an official visitor center.

Many people in Clarke and Frederick counties and the City of Winchester must wonder why the Chamber extended such recognition to me, especially since the Barns opened in 2011 — 13 years ago! It’s because of Jim Wilkins and Donna Downing, and their knowledge of the Barns story, as well as letters of support from a number people who participated in the project with me from 2005 through 2019, excepting 2012 and 2013.

Because it’s a story of determination and of people working together to achieve a desired goal, it may be of interest not only in our area but also in other communities, and I want to share some of it.

My part started in late 2004, when the project was designated a 501(c)3 by the IRS and I was asked to lead the project. We were starting from scratch.

The initial steps were clear: recruit a board of directors, select an architect, design a capital campaign. We knew, too, that strong communication was essential, as were suiting the person to the task, keeping the vision always in mind, raising the visibility and value of the project to constituents as much as we could, and working unstintingly through every challenge that presented itself.

When I say “we”, I mean the board of directors. Although the composition changed over time, the directors worked with high good spirits and strong engagement together.

We spent time developing a mission statement. We identified private and public sources of funding and set about grant-writing and calling on private citizens, foundations, and state and federal representatives. We kept the project in the public’s eye through stories in the Clarke Courier and the

Winchester Star. We offered programs in the arts — we were a “reality without a roof” — with films, costume and fashion shows, pottery shows and sales, music performances. We mailed out thousands of letters. We met regularly with Carter+Burton, our architect and educator in all matters of construction.

We wanted a year-round, multi-use facility that salvaged as much of the original construction as possible, met ADA requirements and had an elevator. We considered energy options such as geothermal and green construction designs.

The funding began to come. Several major donors lent their support. Our third attempt for a VDOT “ICETEA” grant was successful because of the inclusion of a visitor center. Our fourth attempt for a HUD Community Development grant came through with our congressman’s support. A Virginia grant through the Department of Historic Resources had the support of our state delegate. We were persistent in pursuing these.

We learned that federal and state grants required a huge amount of administrative work. We learned that Environmental Impact and Landscape Engineering studies were required, and we took care of it.

The capital campaign started in 2005 and lasted more than six years. Gifts ranged from $5 to $100,000. We raised more than $2 million in public and private funding and in 2010 published an Invitation for Bids. H&W Construction won the day and started work, and we opened to the public in 2011. The facility was beautiful.

I returned then to the job I had before starting the Barns project, and new leadership came in to take the organization into its work as an operating enterprise.

There was a learning curve that kept the Barns from flourishing in its first two years, despite an active events schedule. I had retired in 2013, and I asked the board if I could help. In 2014, I was named chair again, and we established operating committees — in effect, business departments — to see to the organization’s management since we couldn’t afford an executive director. We developed a strong budgeting format and created operating policies and procedures. We focused again on fundraising.

Over the next six years, we stabilized our financial position. We certified the visitor center with the Virginia Tourism Corporation, which required signage on Route 7 and 340, working with VDOT and cost-sharing with the town and county. We became a community partner of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, bringing the museum’s Artmobile to Berryville and working with Clarke County schools to bring kids in to see it. Our programs were drawing larger audiences. Our staff of two managed valiantly.

When we could afford a third staff member, we hired Sarah Ames as our office manager, and two years later promoted her to the position of executive director. She brought superb organizational skills that allowed us at last to transition from an operating board to a governing board, an important transition.

Significantly, we were able to establish two $1 million endowments, which finally brought a sense of financial security and enabled us to pay our dedicated and talented staff what they deserved. In 2019, the Barns drew more than 9,000 people to music concerts, art exhibits, workshops, and many other activities. I stepped off the board at the end of 2019, having served the maximum six consecutive years. Post-pandemic, the Barns is again bringing thousands of people through the doors annually. I hope this bit of history is of some value to other communities with ambitious aspirations. As the 19th-century German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe said, “Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has power and magic in it.”

A roundup of news and community news around Clarke County

Clarke Animal Shelter Has New Hours

The Clarke Animal Shelter revised its hours in March to better serve the animals in its care and the humans who come to visit. New visiting hours are: 10:30am to 4pm Mondays, Tuesdays, and Thursdays; 11am to 6pm Fridays; 10am to 4pm Saturdays. The shelter is closed on Sundays, Wednesdays, and holidays.

Clarke Animal Shelter staff does not travel to trap or collect dogs or cats. The shelter does not accept wild animals. Staff is on site to accept pets surrendered by their owners and strays delivered by individuals or Sheriff’s deputies. Anyone who needs to drop off an animal — surrenders and strays — should first call the shelter, so staff is prepared to receive the animal(s).

Additionally, know which agency to call regarding any stray or lost domestic animal, including livestock, or to share a concern about a wild animal in Clarke County. Different agencies respond to different situations. Go to the Clarke County website, www.clarkecounty.gov, and the “Animals & Animal Shelter” page for more information. Clarke County government manages Clarke Animal Shelter, but the shelter is owned by the Clarke County Humane Foundation, a 501(c)(3) corporation.

Staff and the volunteers who work at the shelter are dedicated to finding permanent homes for all adoptable pets. Adoption fees are $35 for a cat and $50 for a dog. The Clarke Animal Shelter is located at 225 Ramsburg Lane in Berryville. Contact Animal Shelter Manager Katrina Carroll at (540) 955-5104 or animalshelter@clarkecounty.gov.

— Cathy Kuehner

Top of Virginia Regional Chamber to Provide Arising Leadership Program

The Top of Virginia Regional Chamber will offer the Arising Leadership Program (ALP) as a catalyst for the development of a dynamic workforce in the Top of Virginia region. This program cultivates leaders in the arising generation that radiate confidence through awareness and experiential learning.

The program allows participants to explore the diverse facets of the Top of Virginia region’s career opportunities in business, government, and the nonprofit sector. Its goals are to cultivate leadership and communication skills, instill and nurture a sense of civic and social responsibility, and to provide participants with a specific career pathway shadow session. Rising juniors and seniors in public, private and home schools in the city of Winchester and counties of Clarke, Frederick and Warren are eligible to participate, but space is limited. The program is free thanks to its sponsors.

Sessions will cover topics such as leadership and communication, business and industry, community culture and agriculture, government and public safety, and health care and the nonprofit sector. The program ends with career exploration and capstone projects.

Registration is open through April 14 at www.regionalchamber.biz. Additional information is available by calling 540-662-4118 or emailing kfincham@regionalchamber.biz.

Patterson’s paintings at Cosmic Harvest Art Show

Berryville artist Keith Patterson’s artwork will be featured at the 2024 Cosmic Harvest Art Show at The Galleries at Long Branch in Millwood Virginia. The Galleries at Long Branch are a fitting backdrop for the bold and audacious colors, themes and scenes of Keith Patterson’s award-winning original artwork. This all-new exhibit is comprised of 30 never-before-displayed works that range from florals and landscapes to the abstract and outright mystical. Keith has studied and adopted the techniques of modern 19th century artists Cezanne, Manet, and Van Gogh, as well as 20th century masters Matisse, Monet, and Pollock. Much of the inspiration for Keith’s work arises from the natural beauty of Clarke County and in the mountains, rivers, and farms of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

The opening of the exhibit is Saturday, April 6 from 6–8pm at The Galleries at Long Branch 830 Long Branch Lane, Millwood, VA. The exhibit runs through June 30. For information go to www.cosmicharvest.com

Quilt Exhibition Tours the Nation’s Capital through Fiber Art Binoculars

From the fiber artists who brought us Inspired by the Beatles (2016), Inspired by the National Parks (2017), Inspired by Elvis (2019), and Inspired by Endangered Species (2020) comes another exhibition featuring 103 quilts that depict unmistakable landmarks and destinations in and around our nation’s capital. Inspired by the Nation’s Capital will remain on display at the Barns of Rose Hill through April 27.

Interlaced with familiar sights like the US Capital, Lincoln Monument, and the White House, visitors will also find themselves immersed in scenes of the bustling Maine Avenue Fish Market, of kites soaring overhead at the Cherry Blossom Festival, and of pigeons enjoying scraps around brightly colored food trucks. Collectively instilling a sense of pride and patriotism, this clever exhibition will appeal to anyone who has ever visited, lived, or worked in DC.

Galleries at the Barns of Rose Hill are free and open to the public from noon to 3:00 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday, and during events. More information about the exhibition is available at barnsofrosehill.org/exhibits.

Restorative Justice Summit: Shaping a Future of Healing and Transformation

By Brenda Waugh

Two Clarke County residents are taking their talents over the border to West Virginia for a statewide conference to be held in June. The West Virginia Restorative Justice Summit will be held on the campus of West Virginia Wesleyan College from June 14 through June 15, 2024. The summit brings together community members, professionals, and justice-impacted individuals to explore their experiences with the educational and judicial systems and explore options for improvement by tapping into restorative justice. Berryville resident Mackenzie Collins is the conference coordinator, pulling together the speakers, exhibitors and planning for meals, housing, and entertainment. Berryville resident, Brenda Waugh, is on the advisory panel for the organization sponsoring the conference, the West Virginia Restorative Justice Project, and is taking a lead role in organizing the conference.

Brenda and Mackenzie will be joined by another Virginia resident and keynote speaker, Valerie Slater. Ms. Slater, executive director of the RISE for Youth Coalition, will shed light on innovative approaches to address systemic challenges for programs designed to provide services to youth. Her session is titled, “Looking for More Than Accountability to a Justice That Also Restores.”

Professor Kathy Evans from Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg will present two break-out sessions: “The Non-Negotiables of Restorative Justice in the Educational Setting” and “Promoting Healthy School Community Partnerships in the work of Restorative Justice. Jim Nolan, a former police officer and professor of criminology at West Virginia University will facilitate a discussion regarding policing in his session, “Restorative Justice and Police Reform. Federal Magistrate Judge, Hon. Michael John Aloi, who will describe how he brings compassion to his work in his session, “Restorative Justice from the Bench: Not So Random Acts of Kindness.” Amber Blankenship, a formerly incarcerated woman who is now a leader in Re-Entry, will facilitate a breakout session, “REACH back Reentry Navigators – Assisting Individuals Navigating Reentry into the Community”. Over thirty sessions are offered for community members and people interested in learning more about restorative justice. Continuing education credits are being sought for the professional attendees in these areas.

“We are thrilled to convene this summit, providing a platform for dialogue and collaboration among stakeholders dedicated to advancing restorative justice principles,” said Brenda Waugh, a member of the Advisory Group for of the West Virginia Restorative Justice Project. “Through an engaging keynote address, interactive breakout sessions, and meaningful networking opportunities, we aim to inspire actionable change and foster a community committed to healing and transformation.”

In addition to the enriching workshops, attendees will have the opportunity to unwind and connect at a live music event on Friday evening featuring the eclectic sounds of Lua Flora, a band from Asheville, North Carolina.

“Ensuring we have not only engaging speakers, interactive exhibits, and plenty of time for networking, it was important to the committee that we also foster an atmosphere of inclusivity and fun. I believe including a performance by Lua Flora will significantly contribute to setting the desired tone,” said Mackenzie Collins, Conference Coordinator. “Our goal is to ensure everyone has a fulfilling experience.”

The summit will begin at 8:30 a.m. on June 14 and conclude at 5:00 pm. on June 15, 2024. The early-bird registration fee is only $200 and provides attendees with access to all sessions and meals. Low-cost housing is available for an additional cost on campus.For more information and to register for the West Virginia Restorative Justice Summit, please visit wvrjp.org.