Gathering in Unity, Celebrating Diversity

Story by Amy Mathews Amos

Photographs by Jennifer Lee

In the weeks leading up to The Gathering, organizer René Locklear White called it “an experiment in humanity” and a “multi-cultural thanksgiving.” Her experiment included a gourd craft festival sponsored by the Virginia Lovers Gourd Society, a military color guard headed by the Native American Women Warriors, and a Harvest Dance with native dancers in regalia. But at its core, The Gathering was about bringing people together – native and non-native – to celebrate “humanhood” as Locklear White’s co-organizer and husband Chris (Comeswithclouds) White put it. “This is a little off the rails,” said Chris before the event. “We don’t know what will come out of it. It’s like planting a seed.”

On October 30 through November 1, that seed blossomed at the Clarke County, Va. fairgrounds.

Locklear White grew up in a Lumbee tribal community in North Carolina and recently retired as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Air Force. Now, as a member of her regional Council of Elders, she and her fellow leaders felt a calling to hold a traditional Harvest Dance (a Pow Wow-like event) in her current community of Clarke County as a way to bring people together. “There is a saying in the Indian community that we are all related,” she said. “Not just related through genes as humans, but through the elements of the earth.”

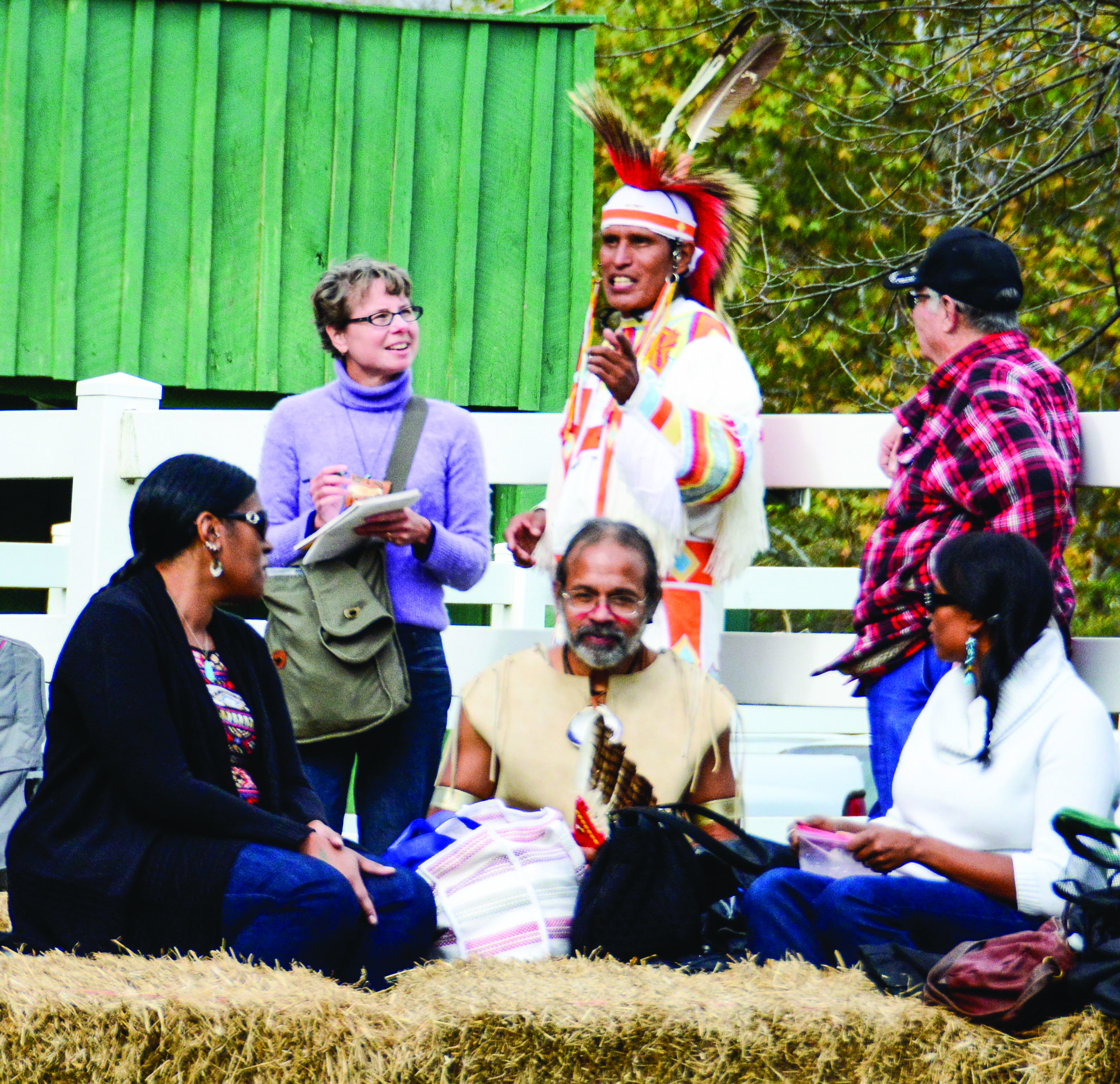

Judging by the diverse, multi-cultural crowd in the grandstand on The Gathering’s second day, many non-Indians agree. Master of Ceremony Dennis Zotigh, a native storyteller and cultural advisor to the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, took the opportunity to educate that crowd about Native American culture. He answered questions from the audience — such as how many Americans self-identify as Indians (about 5.2 million in the 2010 census, or 1.7 percent of the U.S. population); and how Native Americans traditionally used gourds (as utensils, decorations, toys, water containers and more). But he also asked the sea of white, brown and black faces around him a few questions of his own: namely, where had they come from? Not surprisingly, most visitors hailed from Virginia. Some had traveled from out of state. Yet a handful came from overseas – including some from England, Brazil, Germany and Lithuania — drawn to The Gathering as part of their American travels to experience a real Native American Pow Wow.

And experience it they did. Zotigh and his co-host, American Indian civil rights leader Dennis Banks, engaged the crowd throughout the day. They encouraged everyone to participate, particularly in the “intertribal” dances, when the grandstand cleared as people streamed onto the field to join hands and dance together. When the military color guard led by the Native American Women Warriors organization paid special tribute to military veterans, Zotigh called for “all warriors – native or not” to enter the arena and be honored as defenders of freedom. Although American Indians fought the U.S. military repeatedly over the centuries to defend their land from European settlers, Indians are very patriotic today according to Zotigh. He called Indian veterans “defenders of our lands, our life, and our families.”

Throughout the day, four different drum circles took turns accompanying the dancers: the Yellow Child Singers; Storm Boyz of Virginia; Thunderbird Métis Nation Drum, Singers and Dancers; and the Zotigh Singers of Albuquerque, N.M. Native dancers in regalia from New York, North Carolina, Minnesota and elsewhere danced to the drum beats in multiple dance categories, including grass dance, men’s traditional, women’s traditional, jingle dress, and fancy shawl. Zotigh emphasized how different tribes have different traditions, but come together to dance to the beat of the same drum at Pow Wows.

One of those dancers was Clifford Dumarce, a grass dancer in magnificent white regalia decorated with blue and orange beading and topped with a crown of red and brown feathers. Dumarce grew up in the Lake Traverse Reservation in South Dakota, but now lives in North Carolina after 13 years in the Marine Corps. His Indian name is Walks into Battle (translated as zuya wicasta in his native language) and he was at The Gathering with his wife and two young daughters. “We’ve been at a Pow Wow somewhere in the country every weekend since April,” said Dumarce. One of his daughters was participating in the jingle dress dance and the other in the fancy shawl dance. He came to The Gathering to “see a new place, see new people.”

Dancer A’lise Myers-Hall, a retired Air Force veteran and Shawnee and Lenape woman, viewed The Gathering as an opportunity to educate others about American Indian culture. “We need to disavow what people see on television. We’re not John Wayne Indians,” she said. She stressed the diversity among Native Americans and noted that “Pow Wows are one thing that brings us together.” Myers-Hall epitomized that diversity herself, growing up in an immigrant community of Germans, Dutch, French, and Italians in eastern Pennsylvania. Her grandfather was Jewish and to many, Myers-Hall would appear African American. Her Indian name is Two Leaves Dancing, because she was born in November and as a tiny baby was mesmerized by the falling leaves.

Meanwhile, at the Gourd Festival in a nearby pavilion, Peruvian carver Percy Medina joined other artists to display his intricate designs of birds, fish and village life on elaborately decorated gourds. Medina’s gourd art is on permanent display at the Infinity of Nations exhibit at the National Museum of the American Indian.

And out at the food court, Lithuanian travelers Jurgita and Mende Timinskas waited in line for Three Sisters Stew, made with corn, beans and squash. The Timinskas are spending several weeks traveling around the U.S. but were drawn to The Gathering because they enjoy Native American Pow Wows – they’ve been to several already in Germany and the Czech Republic.

Everyone at The Gathering – Peruvian or Lithuanian, native or non-native, veteran or not — could come together in the “round dance.” Zotigh and Banks encouraged the crowd to form a large circle in the arena and hold hands. Then, led by head male dancer Tatanka Gibson the circle collectively stepped to its left, moving continuously clockwise until it circled within itself like a spiral, forming new coils as Gibson kept the line flowing, allowing participants to view the smiling faces winding past them as they moved towards the center. When it could close upon itself no further, Gibson masterfully turned the twisting spiral of humanity in the opposite direction, leading his inner layer outward and bringing the 125 person-long chain behind him, everyone swirling in a new direction, connected to one another physically and visually.

Banks – known for his iconic quote “it’s a good day to die,” during the 1973 siege of Wounded Knee, S.D. as he fought for Native American rights — pronounced the sunny autumn celebration at The Gathering “a good day to live.”

On this day, at least, the experiment we call humanity was a success.