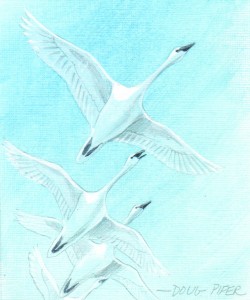

Tundra Swans On Migration

By Doug Pifer

About ten minutes early, I parked the old truck in the gravel lane, waiting for the farmer to load up my hay. As I sat enjoying the quiet, I heard what sounded like a distant dog barking. But then I recognized it as the sound of a migrating flock of tundra swans filtering down though the crisp air of a beautiful November morning.

Immediately I hopped out of the truck, scanned the blue sky and listened. I finally  picked out a twinkling silvery V. A couple dozen tundra swans were just visible for a few seconds. They were very high, almost at the limits of my vision. I clearly heard their high bugling cries as they circled, then disappeared momentarily. They had turned away from the light, rendering themselves momentarily invisible in the slanted morning sun.

picked out a twinkling silvery V. A couple dozen tundra swans were just visible for a few seconds. They were very high, almost at the limits of my vision. I clearly heard their high bugling cries as they circled, then disappeared momentarily. They had turned away from the light, rendering themselves momentarily invisible in the slanted morning sun.

Then they reappeared, headed in a different direction towards the Potomac River which flowed just a few miles away. Now directly overhead, the V formation stretched. I easily counted twenty-four long-necked, flapping birds. As they passed over they changed their flight pattern, stretching out into a curved line. Then they disappeared into the southeastern sky, their calls still ringing in my ears.

Tundra swans are a wildlife conservation success story. In 1900 these all-white migrants from the north were called whistling swans. By that time they had been all but wiped out, shot by hunters as they migrated to their Atlantic Coast wintering grounds. There was little hope for their survival.

Hunting seasons became regulated, and it was illegal to shoot swans. Almost immediately, swan populations began to rebound. Then in the 1960s, just as the swans had begun to build their numbers up, industrial pollution of their wintering grounds nearly wiped out their winter food supply of eel grass or wild celery. But instead of succumbing to extinction, the swans adapted and changed their eating habits. Instead of the eel grass that used to grow in coastal waterways, they began to fly inland each day to feed on waste grain and winter wheat in agricultural fields. Whistling swans, presently known as tundra swans, are now among the most abundant waterfowl wintering along the Atlantic coast.

Over the years, waterfowl biologists have tried various ways to track the movements of swans between their breeding and wintering grounds. They first captured the birds on their breeding grounds and attached plastic sleeves onto their necks to mark and track individuals. This made it easier to track where they went but not the migration route they took. The biologists eventually determined that small satellite transmitters placed on the birds’ backs allowed them to be tracked over long distances with a minimum of stress.

Today, tundra swans can be seen all winter along the coast from the Chesapeake Bay to South Carolina. In the fall they begin passing over here at the beginning of November, and they leave their wintering grounds in late February. And swans can once again be hunted in limited numbers in many states.

So if you hear what sounds like a distant pack of hounds this time of year, look up. You might see a flock of wild swans.