Bennett Russell and Others vs. Negroes Juliet and Others

In 1850 one of the most hotly contested court battles in the area, if not in the entire state of Virginia, began its long journey through the courts and was not resolved until 7 years later in 1857. What made this particular court case so unusual were not only the defendants but what they were defending. The defendants were slaves. Their argument was the most basic of human rights. Freedom.

In 1848, a large landholder and slave owner in the northwest part of Clarke County, died. His name was John Russell Crafton (1772-1848)* and in his will he not only left his 2,000 acres to be equally divided among his heirs, but he also named a large number of his slaves to be freed upon his death. Among those slaves named to be freed was a young black woman known only by the name of Juliet. She had known what was in the will, but she did not know that a later addendum to that will, known as the “Articles of Agreement,” had been added to the will June 13, 1842. It not only revoked their freedom, but instructed the heirs to sell the slaves upon Crafton’s death.

Juliet was not going to be deterred from her fight for freedom, and forced the heirs of Crafton’s estate to bring suit against Juliet and others who had refused to accept that Crafton had reversed his initial desire that she and others be freed.

It does seem odd that John Russell Crafton would have changed his mind about freeing these slaves. He had been raised by his mother’s family (his mother Ann Russell had died shortly after his birth) in Loudoun County, Va., and his grandmother had been a Quaker. As has been well documented, Quakers saw slavery as immoral. It would have been natural that John Russell Crafton would have been, at least in part, influenced by his grandmother. Although he had been a slave owner, there may have been a residual guilt of owning another human, and to rectify such he therefore made the late moral decision to free his slaves upon his death.

In 1839 John Russell Crafton had provided in his will the freedom of his slaves and any children that may be born prior to his death. Their names, with their ages as given in 1850, were as follows: Juliet (35), Moses(30), Amanda(17), Fanny(16), Harriett(13), Marshall(12) and all their children, named Rachael(4), Mary Jane(19), Granchison(8), Thomas(7), Wenny(4), Emily(2) and two infant children, one the child of Amanda and the other a child of Mary Jane. The total persons declaring their freedom was a total of 14 slaves.

Two years after John Russell Crafton’s death, the court case was filed in the Clarke County Court House by Bennett Russell, curator for the estate of John Russell Crafton. The year was 1850 and in 1851, the court was moved to Frederick County, Va. No doubt, the venue was changed by the request of the attorney representing Juliet and others. With Clarke County being a far larger slave-owning county than Frederick County per capita, and the fact that Bennett Russell, curator, was not only well known in Clarke County but was also a Gentleman Justice of the local courts, the attorney for Juliet did not feel that a fair trial could be had in the local court.

How Juliet was able to convince any local attorney to take their case is not known, but it does not seem possible that Juliet would have had the resources to pay an attorney. The local attorney who represented Juliet and the others was Richard Parker. The Parkers were an old family in Clarke County who had lived for several generations at their home between the Blue Ridge and the Shenandoah River known as “The Retreat.” This stately old home still stands today and the development, Shenandoah Retreat, next to it was named for the home.

Thus began a court case that Cartmell’s book, “Shenandoah Valley Pioneers and Their Descendants” described as, “…a torturous course through the courts…..attracting large crowds of people to every trial.”

In the 1850s the abolitionist movement was reaching an all-time high. The winds of war were already being felt. The wealth of the South had been built upon the backs of slavery. Ending slavery meant ending their wealth and power. There was no doubt that the area residents, as well as others throughout Virginia, followed this court case with intense interest. How the court eventually ruled on this case would have reverberations throughout the land.

Slavery had from the beginning been questioned as a moral issue but now, a small but vital part of the slavery question was being addressed in a court of law. For the slaves involved in this court case, it was far more than a legal precedent. It was simply freedom versus continued bondage. For slave owners everywhere, the case was viewed as a possible chink in the legal armor of slavery laws. The court had already, knowingly or not, acknowledged the right of a slave’s voice to be heard in a court of law and question those who enslaved them.

John Russell Crafton was an old man in 1842 when these Articles of Agreement were signed and although my research has not yet proven so, there are questions as to the health and “soundness” of Crafton’s mind when he signed the Articles of Agreement — if indeed he had actually signed such an agreement. What is known, the courts took 7 years in which to answer this question. This was an unusual amount of time to spend in court for what many thought would be an open and shut case in favor of John Russell Crafton’s heirs.

In 1857, the court finally rendered a verdict. It was the court’s opinion that the Articles of Agreement was to be considered the Last Will and Testament of John Russell Crafton, thus ending the slaves historic and heroic 7-year battle for their freedom. Per the directive of the Articles of Agreement, the slaves were sold.

How could a man who initially had left his slaves their freedom turn around and not only revoke their freedom but make the decision to break this family up by selling them? The answer to this question will never be known for sure and we are left to only speculate.

Two years later, in 1859, a lanky, bearded man with intense eyes and severe countenance passed through this county, stopping at large estates to repair clocks. It has been said that he was often found conversing with slaves on the farms he visited. This strange and intense old man had, within months of passing through Clarke County, become the leader of a slave rebellion that ended in his capture after a short, but bloody, fight at Harpers Ferry. The old man’s name? John Brown.

John Brown’s trial was held in Charles Town, Va. (now West Virginia). The judge who presided over his trial and sentenced him to hang was none other than Richard Parker, the attorney who had for seven years fought for the freedom of John Russell Crafton’s slaves.

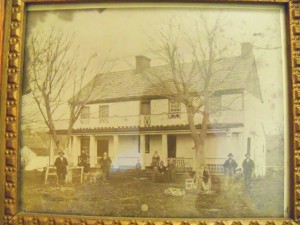

*John Russell Crafton’s father was Major Bennett Crafton from King William County, Virginia. Other than the signing of his marriage bond and his Last Will and Testament, he informally went by the surname Russell. All of his children went by the surname Russell as they became adults. John Russell Crafton is the 3rd great grandfather of the author of this story; and Bennett Russell was his 2nd great grandfather. The name of the family farm was Rock Hall, and the old home first built as a log cabin and later added a stone wing was torn down in the early 1990s. A photo of the old home and Bennett Russell was taken in the late 1850s to 1862.