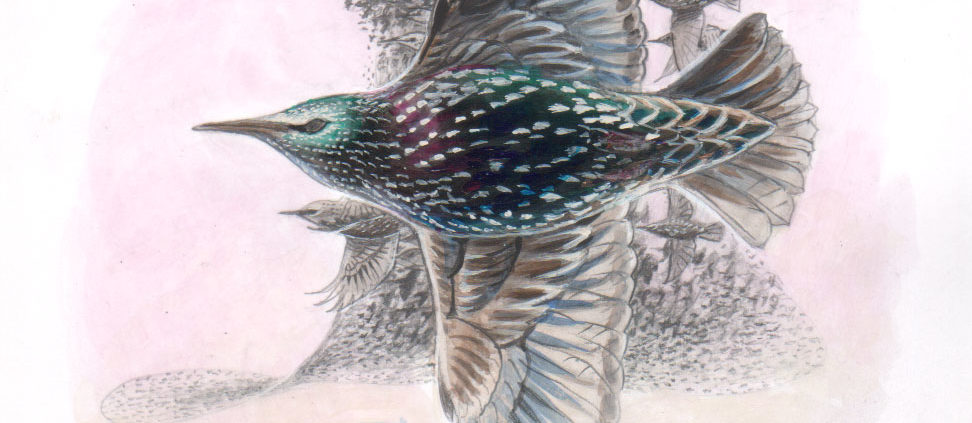

Miraculous Starling Murmurations

Article and illustration by Doug Pifer

An enormous flock of starlings hung around our neighborhood two weeks before Christmas in 2017. One morning I decided to record a video from our bedroom widow of the flock assembling by the hundreds in our back paddock and yard. Masses of starlings performed in unison as the flock seemed to summersault along. Wave after wave of birds landed momentarily as those behind them flew over their heads and landed in front of them.

Then, as if on command, the entire flock took off and flew past the window. The curving stream of birds swirled gracefully away in a continuous mass. The roar of their wings reached my ears where I stood inside the closed-up house. The flock darkened as it bunched, turned, and then lightened as the birds spread out and changed direction. It resembled a single organism convulsing and moving across the sky.

Originally coined as a collective noun meaning a bunch of starlings, “murmuration” now refers to a flock of hundreds, even thousands, of birds moving through the sky in a series of highly coordinated patterns. Other birds, including shorebirds and even common street pigeons, murmurate.

A quick search online reveals many dramatic starling murmurations. One article, posted by Barbara J. King on NPR in January, 2017, features a short but magnificent clip of a gyrating flock of starlings at Cosmeston Lakes in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales.

How the birds do this has been studied intensively by physicists. Over the past fifteen years it’s been pretty well determined that the synchronized movements of a murmurating, pulsating flock of birds is based on the speed, direction, and spatial orientation of just six or seven individuals flying adjacently. These individuals convey this information, which moves through the entire flock almost instantly. Various computer models and studies have managed to determine how birds murmurate and apply it to everything from film animation, traffic movements, and how quickly our own brains operate in relation to others

Much more is known about the “how” than the “why” of murmurations. Many naturalists have observed flocks of starlings murmurate when a predator such as a hawk or falcon attacks. I’ve seen a flock of starlings bunch together and zigzag when chased by a cooper’s hawk. Bunching tightly and then twisting and turning in unison makes it hard for the aerial attacker to pick an individual target, and the attacker gives up.

Other reported instances where murmurating flocks seem to attract predators complicates the predator avoidance theory. It’s recently been postulated that the passenger pigeon, which once roamed the Unites States in enormous, gyrating flocks, has become extinct because they needed the presence of very high numbers of their own kind in order to murmurate and survive. Could murmuration be essential to the survival of starlings?

Consider this if you see a murmuration of starlings!Illustration used courtesy of Pennsylvania State Game Commission.