The Mysterious Bloodroot

The Mysterious Bloodroot

The Mysterious Bloodroot

By Doug Pifer

If you tramp the woods in early spring while it’s still freezing at night but the days start to warm up, you might run across a colony of one of my favorite spring wildflowers. Your timing has to be just right, because the milk-white flowers of the bloodroot last only a couple weeks.

Bloodroot is among the earliest spring ephemerals—delicate, low growing wildflowers that carpet the woods just before the trees leaf out, and then go dormant for the summer. It gets its name from the fleshy rhizome that spreads just below the ground, creating colonies of plants. Picked, cut, or broken, the reddish rhizome “bleeds”—exuding dark sap the color and texture of blood.

For many years we were tenants in a farmhouse at the end of a long lane that wound uphill through the woods. There among the limestone outcrops, bloodroot bloomed every spring. First a few flowers, then the entire colony would whiten the woods like a lingering snow patch between the rocks. Since then the farm was sold and the entire hill—woods, rocks and all—was bulldozed and leveled to create a gigantic warehouse. Our flowers are no more.

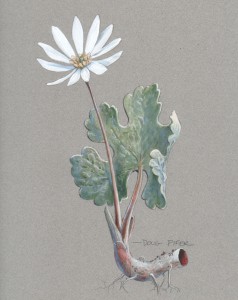

The bloodroot’s beauty is both graphic and sculptural. First a rolled up leaf pokes through the leaf littered soil like a gray-green, rolled up cigar. Before it completely unfurls, a single stem and flower bud pokes up along the center. The flower opens about 5 inches above the ground while the leaf is still curled around its stem. Eight to sixteen white petals radiate from the bright yellow reproductive parts. On sunny days, the petals make a sunburst up to 4 inches across. Otherwise the flower remains closed. Individual flowers last only two days, and in a week or two the whole show is over for the year. A seed capsule forms atop the spindle-straight stem while the lobed leaves, still dull green, open to the size of a human hand. Their texture is pebbly on top, veiny underneath.

By summer, the bloodroot’s leaves wither, and the seed capsule turns yellow and falls to the ground. The plant goes dormant but the cycle is far from over.

Seeds of bloodroot have a fleshy coating that attracts ants. The insects carry the seeds into their underground colonies where they eat the fleshy part. The seeds then germinate, having been planted and fertilized with “frass” (a rich combination of insect parts, ant poop, and ant garbage) by the ant colony.

Known as Sanguinaria to scientists and herbalists, bloodroot’s medicinal value isn’t well studied or understood. Native Americans reportedly used it to cure rheumatism, as face paint, and as a love potion. (If a young man secretly marked the hand of his intended with bloodroot juice, she’d agree to marry him in two weeks).

Bloodroot components have been used commercially in mouthwashes and toothpaste, but full strength juice can damage the skin. Several folk healers have gotten into trouble in recent years after administering Sanguinaria as a cancer cure.