Preserving History and Restoring Nature at Cool Springs

Preserving History and Restoring Nature at Cool Springs

Shenandoah University’s plans for Civil War property keep the focus on low-impact educational activities

Colleen Lentile

On any given day, passers-by could walk by Shenandoah University’s main campus in Winchester and see students and nearby residents wandering about, using the property as their own. Those same students and locals now can be found on SU’s fifth campus, the River Campus, located at the Cool Springs Battlefield on the Shenandoah River in Clarke County.

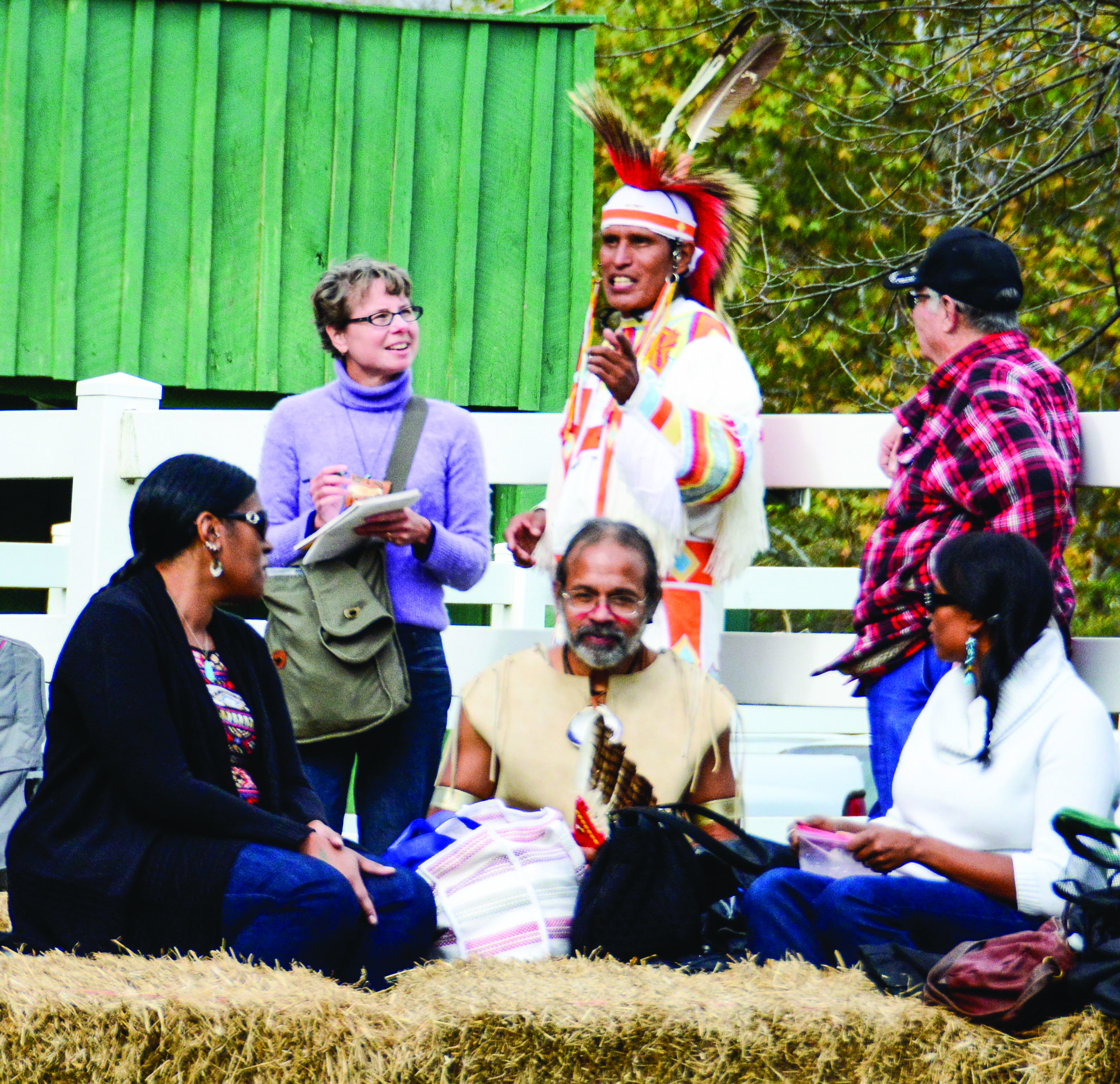

Cool Springs, once the Virginia National Golf Course, was given to SU through an easement with the Civil War Battlefield Trust in April 2013. The easement guarantees a perpetual conservation plan—but the specifics about how the land will be managed, and for whose benefit, was a matter for the university to determine. SU’s current plans for the property include an “outdoor classroom” for their students, focusing on the educational assets that come along with the property, including the historical, environmental, and cultural aspects of the land.

From a conservation perspective, the most compelling element is the ground’s Civil War history. On July 17–18, 1864, only seven days after the Battle of Fort Stevens, Confederate Lt . Gen. Jubal Early left Washington, D.C., and retreated into the Shenandoah Valley. Upon President Lincoln’s request, Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright followed in pursuit of Early and his men, who were left without Gen. Robert E. Lee and his soldiers. With Brig. Gen. George Crook’s army by his side, Wright led 10,500 men after Early. Wright caught up with Early at Snickers Ferry and the two sides collided near Cool Springs, leaving approximately 800 casualties.

The university’s Cool Springs project, now nicknamed “Shenandoah on the Shenandoah,” is overseen by the Dean of the College of Arts and Science, Dr. Calvin Allen. He says he is in constant communication with everyone involved in the project, insuring that current activities run smoothly and future activities are planned in accordance with the easement and the university’s education mission. Onsite management is carried out by Gene Lewis, the Cool Springs property steward and manager, and T. Grant Lewis, the Cool Springs program director. Allen plans to incorporate the property into student life programs, including the outdoor leadership.

The school says it’s also working closely with the Clarke County communities around Cool Springs, including the Holly Cross Abbey and the Shenandoah Retreat, and Clarke County and regional historical groups. The residents of the Retreat have the same access as others and received the code to the locked gates when the project began with SU.

The Shenandoah Retreat Land Corporation board of directors remains positive about the situation as well: “[We have] enjoyed proactive and positive communications with Shenandoah University,” said a member of the Retreat’s board. Just like anytime you get a new neighbor in your neighborhood, there is a ‘get-to-know-you’ period, and we reserve concerns for our community. We are pleased to find that the university and the Retreat have mutual interests in fostering a long-term relationship.”

T. Grant Lewis says the university tries to be a good neighbor. They are aware of the noise that they create; they try to keep in contact with the residents around them, and will enforce the 15mph speed limit in the Retreat. They also are only using one road, Parker Lane off of Route 7, for access into Cool Springs.

There are two structures at Cool Springs: the Clubhouse, which is the only historical building on the property, and one small pavilion. There are a few gravel parking lots, a walking path, and 195 acres of open land and river.

Allen, Lewis, and Lewis told the Observer improvements include some interpretive signs describing historical significance, but there are no plans for construction except for a few outbuildings like rest rooms and a covered weather shelter. Lewis and Lewis also mention that they personally don’t want to see anything built there.

Cool Springs is now open to students and the public from dawn until dusk every day, with exceptions for events like star gazing. Everyone at Shenandoah University stresses that while the public is welcome, Cool Springs is not a park—it is a natural area of historical significance. “It’s not a free-for-all,” said T. Grant Lewis, commenting on student access to the land.

Cool Spring’s rules and regulations are posted on signs placed about the property. No hunting, firearms, or metal detectors are permitted. Lewis and Lewis are putting their trust in SU students and the public to respect the Cool Springs property and adjacent neighborhoods.

“Cool Springs will have the same openness as our campus,” said Dr. Allen, referring to the citizens that walk and bike on the main campus in Winchester.

“The overall goal is to get the property back to what it was in the 1860s,” said Dr. Allen. Specifically, there will be no golf course. Cool Springs will be managed as a nature reserve.

Lewis and Lewis refer to the Cool Springs property as a “wonderful gift,” hoping that the students and community will “connect to the land,” referring to recent trends in which young people have little or no contact with nature and, as a result, have little appreciation for it.

For Grant Lewis, the long term future of the landscape is what’s most important. He says it will take collaboration and community support to take care of Cool Springs in perpetuity. “Why don’t we get together to protect this place?” he said.

The SU community is already enjoying the Cool Springs land. Recently the Class of 2017 ventured there for a program; and the university’s resident assistants and resident directors had an outdoor retreat there.

While Allen, Lewis, and Lewis all play different roles in determining the future of Cool Springs, each shares a sense of passion about making it work for the community and the resources protected by the easement. They admit to learning as they go, and say that addressing public concerns is not a one-time thing—it will be part of the ongoing management of Cool Springs.

Ultimately, say Lewis and Lewis, they hope that the students of Shenandoah University and the communities around Cool Springs will “take ownership for this place,” and help the land rehabilitate itself, in a community effort to pay it forward for the generations to come.