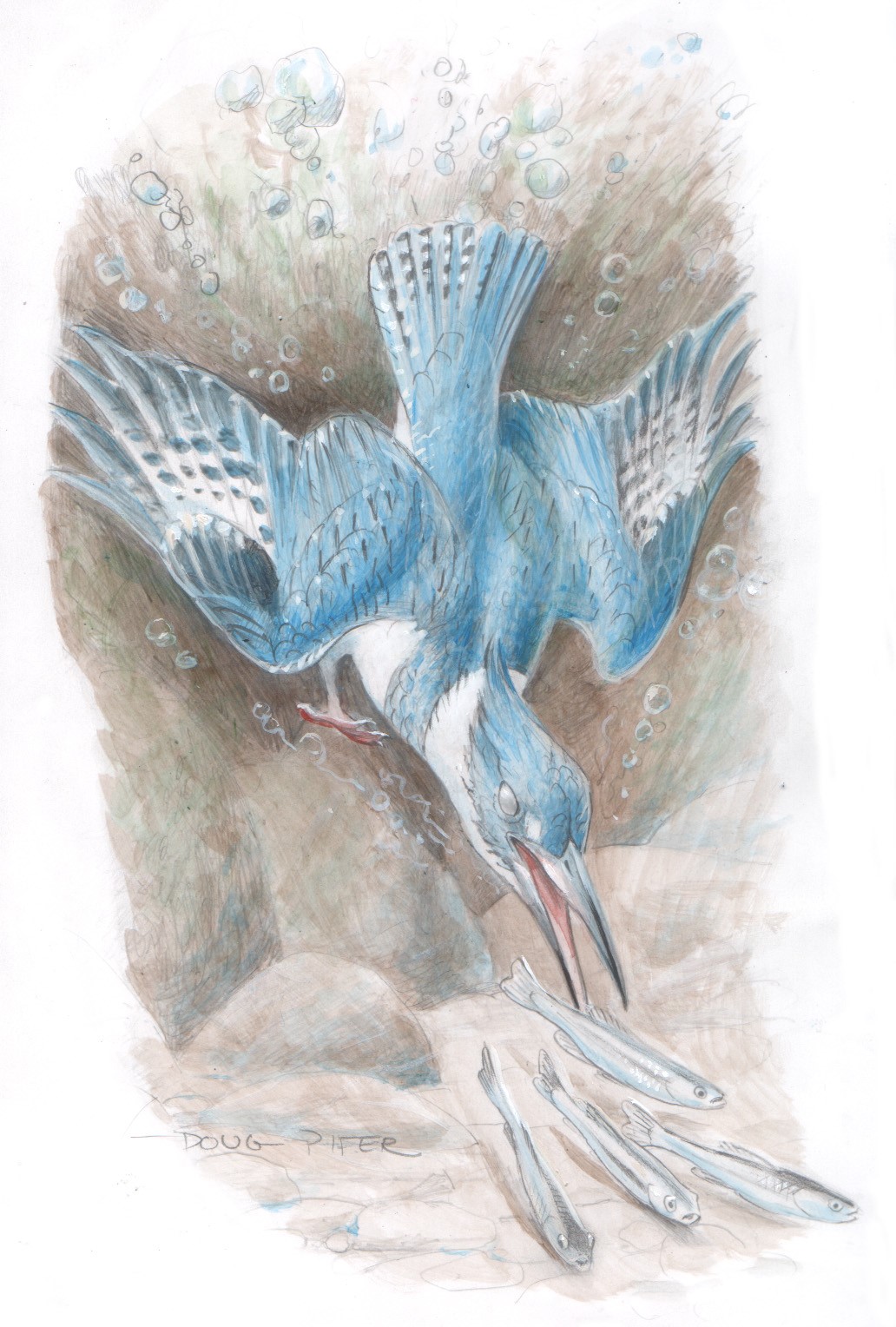

A Visit By Waterfowl Royalty

By Doug Pifer

Almost daily I pass a spring-fed pond on the west side of Route 340 near Waterloo. Despite its small size, it’s a great roosting and feeding area for waterfowl because it stays unfrozen and has a rich crop of watercress. Last week’s storm prompted a visit by waterfowl royalty—two canvasback drakes.

The canvasbacks stood out dramatically because of their dazzling white backs. Set off by a black chest their deep coppery heads shone like a new penny in the sun. Their long, wedge shaped heads sloped regally to the tapered black beaks. Through binoculars I saw ruby eyes and those finely penciled markings on their white back feathers that give them their name. Nearly a third larger than the mallards nearby, they were a treat to watch as they rested and dived after watercress on their way to their breeding grounds.

Canvasbacks played an important role in wildlife conservation history. From early Colonial days to the 1890s, canvasback was a famous menu item in fine hotels and restaurants along the East Coast. They were prized because they were meaty (adult drakes are much heavier than a mallard), plentiful, and well fed.

Diving ducks, canvasbacks prefer to feed on an aquatic plant called wild celery or eel-grass (Valisneria). In those days wild celery grew so thickly in East Coast waterways that it made parts of Chesapeake Bay hard to navigate. Rafts of canvasbacks spent every winter there.

Shooting ducks for sale in the market was a seasonal profession for watermen. They used low-floating “duck boats” equipped with cannons hidden below a flat roof that was covered with wooden decoys. Market hunters sold hundreds of ducks a day to restaurants and markets. By 1900, canvasbacks were rare.

At that time Congress passed the Lacy Act, which gave Federal protection to migratory birds and outlawed market hunting of all wildlife. Hunting was closed on canvasbacks. Despite these measures, canvasbacks faced new problems in the 1960s. Polluted waters of coastal waterways no longer grew the wild celery plants they ate. Many waterfowl also died from ingesting spent lead shot while feeding in muddy waters.

Canvasback numbers rebounded in the 1980s and 90s. Polluted waters along the Chesapeake Bay were cleaned up, and sportsmen’s organizations such as Ducks Unlimited created new nesting habitats on the ducks’ mid-western breeding grounds. Duck hunters were required to use steel shot instead of lead in certain areas. Now you can even hunt canvasbacks in some states.

The ducks, too, have adapted to the times. They’ve switched from wild celery to eating more mussels and clams. On nice winter days canvasbacks can be seen grazing on winter wheat in fields along the Eastern Shore, swimming in the Annapolis harbor—or visiting a little pond in Clarke County on their way north.

It’s great to see canvasbacks again.